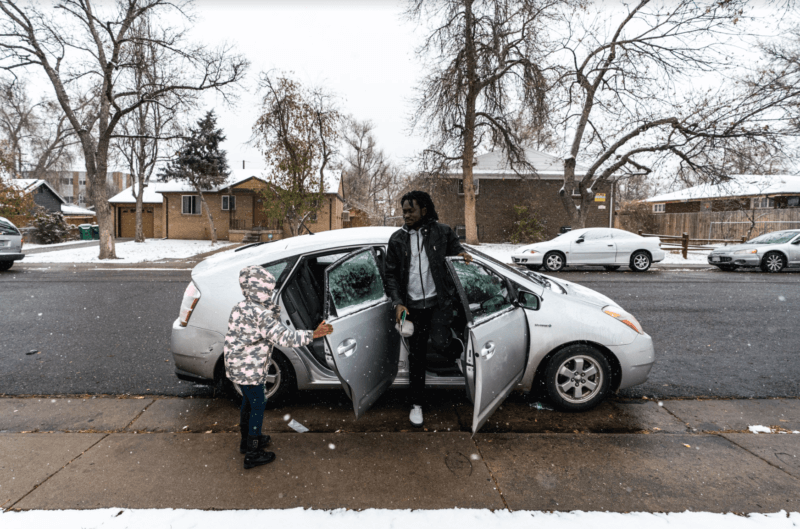

Just one of the hundreds of unique and beautiful families who are integral to our community, Lomami, Chance, and Michaela have been a part of Project Worthmore since their arrival from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018.

Through images accompanied by narratives written by our Board Vice-Chair, Jamie Laurie, we hope these snippets help to provide insight into the lives of refugees and the richness of connection. Photos by Samantha Hines.

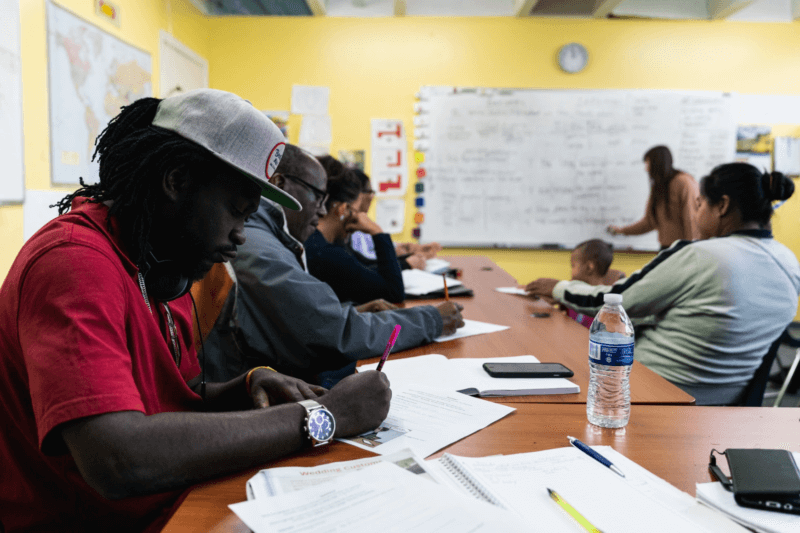

I first met Lomami and Chance when I was volunteering in the English classes at Project Worthmore. Knowing next to nothing about the culture of Eastern Congo, it took me several rounds of questions just to understand their names. She went by Chance, her first name. He preferred to be called by his last name, “Lomami” which is also the name of a large river in the Congo.

It wasn’t until the end of the class that I realized they were a couple. Communicating across language and culture, even the simplest things are not so simple.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Meeting Lomami and Chance gave me a window into their world, helping me understand how every day brings a new set of messages to decode and dynamics to navigate. The language barrier was only the beginning.

When their car’s check engine light came on, we went to Auto Zone together.

When Lomami learned of a non-profit selling discount computers to refugees, we went together to investigate.

When classes were canceled on the anniversary of the Columbine tragedy because of a credible copycat threat, I tried my best to explain.

When Michaela’s elementary school sent a letter to parents asking them to bring food to celebrate their teachers, they asked me to join them for the celebration. But it turned out there was no party. The school just wanted parents to drop off the food.

What a strange and confusing place this is.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

This past spring Lomami had shoulder surgery. He had been living with the constant pain of a dislocated shoulder for more than 7 years.

When I went to the hospital waiting room, Chance introduced me to her brother. I was surprised. I didn’t know she had a brother. I asked to confirm this several times.

Over and over she and Lomami referred to him as their brother. But I began to wonder.

Later, I asked the interpreter at the hospital if she believed they were in fact blood relatives or simply supportive neighbors. She said it was impossible for her to tell with people from East Africa, because of the way they talked about family. The line between neighbors and family are blurry, as are the expectations. Neighbors support each other like family.

The man at the hospital was not a blood relative. He was a neighbor. But he was by their side during surgery, in the middle of the night, missing sleep before a long shift. He was their brother.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sometimes Lomami calls me to ask for advice. But more often he calls me just to talk. The first few times he did this I was confused.

“How are you? How is your mother? Long time no talk.” He would say.

“What exactly does he want?” I thought to myself “What does he need my help with?”

Soon I realized the truth about these calls, and a truth about my own culture. I am accustomed to communication that is oriented around goals. But Lomami’s frequent calls were about something more fundamental. His primary goal was to maintain a relationship he valued.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

I noticed one day that Lomami referred to his wife in Swahili as “Mama Michaela” (Michael’s mother). The more I listened, the more I heard them using their daughter to refer to each other, or other relatives, even when Michaela was not involved in the story.

What does a naming convention like this say about a culture?

What does it say to the child to know you are valued in this way?

I don’t know for sure. But I do know that it makes me feel all the more grateful for the name they have come to use for me: Uncle Jamie.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

On my most recent birthday, Lomami stopped by to ask me a question. “What are you going to wear tonight on your birthday?” He asked intently. I motioned at the clothes I was already wearing. “I will buy you an outfit”, he said. I insisted this was not necessary. He insisted it was. “In the Congo, you must wear new clothes on your birthday”, he said, taking down my sizes despite my objections.

He asked me about my shoe size. “You don’t have to buy me shoes!” I insisted. “Don’t worry about it”, he replied.

But I was worried. I was supposed to be helping him, not the other way around. Plus, for the next few hours I sat with the knowledge that whatever he brought me, I would have to wear. No matter how I felt about it.

But there had been nothing to worry about. The outfit he brought me was, of course, far more stylish than anything I’d ever bought myself.

I looked good on my birthday. And I owed it all to my brother.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

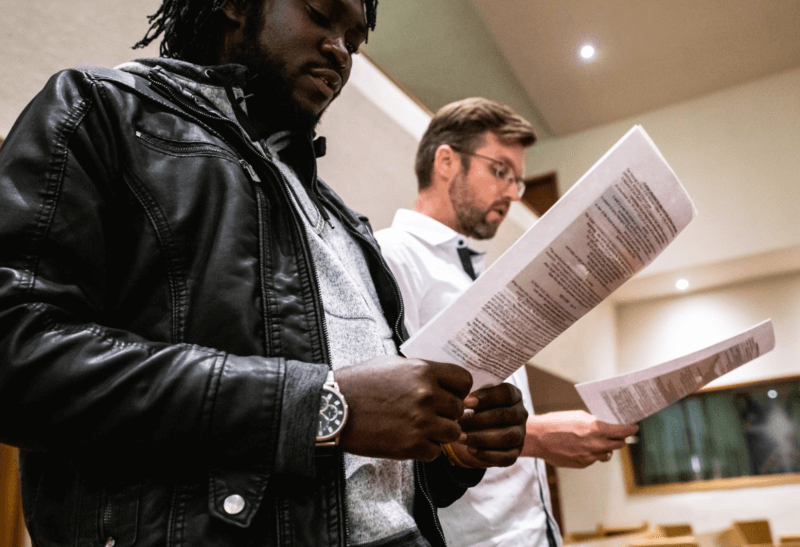

The first day I spent with Lomami we exchanged some rap verses. I learned later that he used to be a part of a dance troop in the DRC. I’m also a rapper myself, an emcee for the band Flobots. Over the last few months we haven’t talked as much about music. But recently he asked me if we could write a song together.

We sat down at his dinner table and he started writing quickly in Swahili. I looked at the lyrics and began translating them in my head.

When I came here I did not have any direction

Then one day, I was sent to school

That’s when I got the news

About people who help refugees

With food, classes, and even the search for work….

As I beat on the table and sang the lyrics, I reflected on what we were creating together. It was more than a personal testimonial. It was an ode to Project Worthmore.